Ideas

Jan 2026

Type

IdeasArticle by

Domenic Cerantonio

Victoria’s town planning system is under growing strain. Lengthy delays, bureaucratic bottlenecks, and unpredictable decision-making are increasingly frustrating homeowners, developers, and local communities alike. Councils, tasked with balancing complex community interests, are often under-resourced and overwhelmed. Meanwhile, the pressure for faster housing delivery and more efficient urban development continues to mount.

Australia is facing a serious housing crisis, with housing supply shortages driving up prices and locking many Victorians out of the market. Every unnecessary delay in approving new homes and developments compounds the problem. At the same time, development costs are escalating — not just from construction expenses, but from the hidden costs of navigating slow and inconsistent approval processes. Holding costs, consultant fees, design revisions, and legal battles caused by delays all contribute to higher final prices for buyers and renters.

If we are serious about solving these challenges, it may be time to consider an idea that, until now, has remained off the table: privatising the town planning approvals process.

Today in Victoria, town planning approvals are largely handled by local councils, with VCAT (Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal) available to review disputes. Councils interpret planning schemes, assess applications, and decide who can build what — and where. In theory, this localised approach ensures decisions are made close to the communities they affect. In practice, however, the system is too often slow, inconsistent, and vulnerable to local political pressures.

Privatising the approvals process — not the planning rules themselves — would mean accredited private professionals, much like building surveyors today, could assess and determine planning applications against the council’s established planning scheme. Councils would retain control over setting policy, zoning, and strategic planning directions. But the task of administering applications — particularly for lower-risk developments — could be outsourced to regulated private operators.

Victoria has already seen the benefits of this kind of reform. In 1994, the state successfully privatised building permit approvals under the Building Act 1993, allowing independent private building surveyors to issue permits alongside councils. This reform delivered faster approvals, improved consistency, and gave applicants real choice — all while councils retained their vital enforcement and oversight roles. The privatisation of building approvals is now a well-established and largely successful part of Victoria’s system, and it provides a clear model for how a carefully regulated private planning approvals market could work.

The potential benefits are significant.

Private assessors could deliver faster decisions, reducing the costly delays that currently plague applicants and drive up housing prices. A competitive system would incentivise professionalism, consistency, and customer service — areas where the current system often falls short. Councils would be freed up to focus on the important work of strategic planning and enforcement, rather than processing endless paperwork.

Privatised approvals could also depoliticise decisions. Currently, even minor applications can become mired in local politics, with councillors under pressure from vocal community groups. A regulated, independent private sector could apply the planning rules more consistently and impartially, focusing on technical compliance rather than political expediency.

There is also a compelling fiscal argument for change. The Victorian Government is facing record levels of debt, with borrowing expected to exceed $187 billion in the coming years. Shifting the administrative burden of planning approvals to private providers would reduce costs for councils and the state government alike — lowering the need for staff, infrastructure, and administrative overheads. At a time when every dollar of public spending must be scrutinised, privatising planning approvals offers a pragmatic, cost-saving reform.

Naturally, there would be concerns.

Critics would point to the risk of conflicts of interest, with assessors potentially inclined to favour applicants who pay their fees. But these risks are not insurmountable. Robust accreditation standards, random audits, strict penalties for misconduct, and a strong centralised oversight body could all form part of the regulatory framework — much like the systems that already exist for private building surveyors.

There would also need to be clear limits. Privatisation would initially be best suited to simple, code-assessable applications — developments that clearly comply with all applicable planning rules. Discretionary, complex, or controversial applications should remain with councils or independent panels to ensure community input and democratic accountability where it matters most.

Privatising planning approvals would not solve every problem in Victoria’s planning system. But if designed carefully, it could dramatically improve efficiency, reduce costs, unlock new housing supply, and help address the broader affordability crisis.

Big challenges require bold thinking.

It is time for Victoria to ask whether holding onto a monopoly over town planning approvals is helping — or hindering — our ability to build the communities we need.

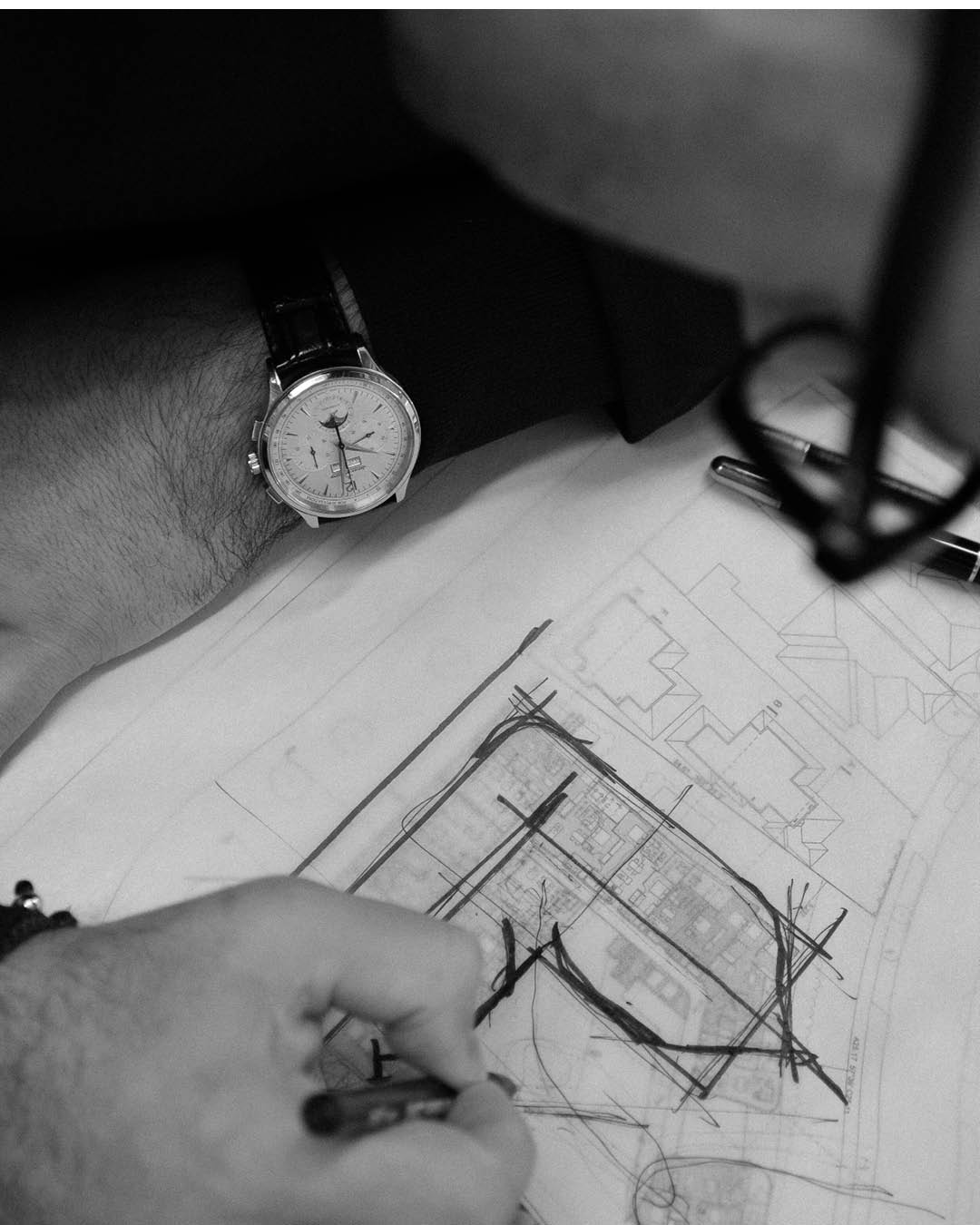

If we are serious about building a better Victoria, we must be prepared to rethink who holds the red pen.