Ideas

Jan 2026

Type

IdeasArticle by

Domenic Cerantonio

It is also the skill that separates many architects and interior designers from our peers in the industry. I don’t believe we are necessarily taught this talent directly at university–after all, there is no course for ‘3D Vision 101’. Rather, it is a skill acquired through hours of vigorous architectural training, and painstakingly honed through real-world practice that trains the brain to have a level of spatial awareness and understanding of spatial flow, circulation, and other design elements that goes unmatched.

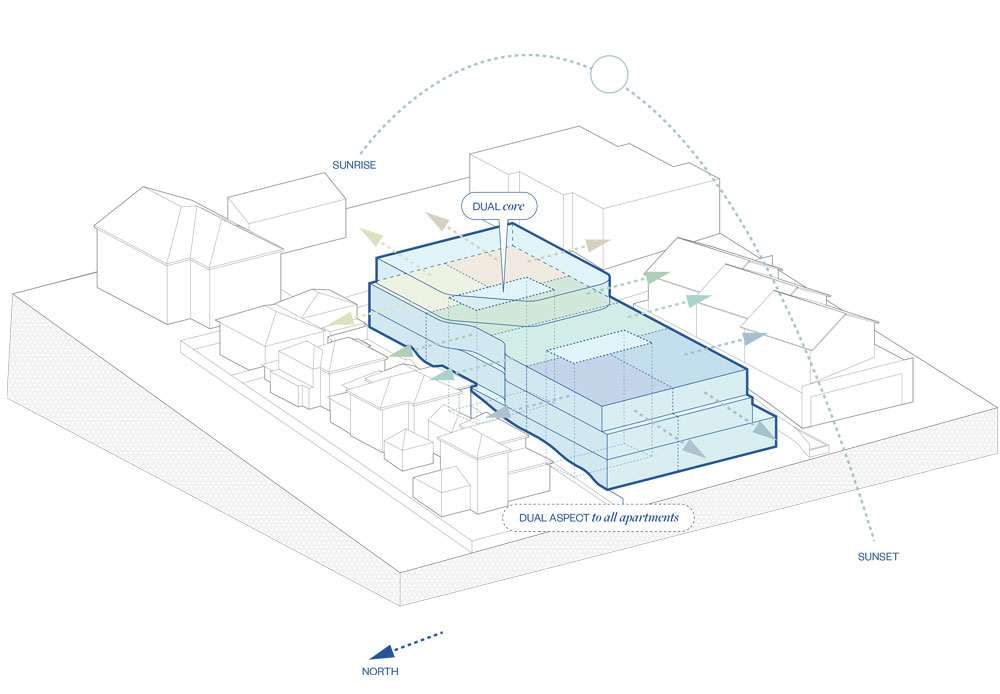

The Better Apartment Design Standards were introduced in 2018 as a way to combat poorly designed apartments in Victoria. Since its inception, there is no doubt that this initiative has brought about a vast improvement to quality of living in contemporary apartment buildings, and this is a very good thing. What’s more, these standards are also contributing to a shift in how we envision living in the future. Better designed apartments and more sustainable buildings have the propensity to make apartment living not only a viable alternative to the white picket fence and quarter acre block, but rather one that is preferred. Again, this is a good thing. The design purist in me will always champion less red tape, however I won’t deny BADS the kudos it is due.

That said, I can’t shake the feeling that while BADS has undoubtedly raised the bar for the lowest common denominator, it has simultaneously clipped the wings of those of us who strive to deliver more creative and innovative multi-residential design schemes.

Whilst the standards are fairly prescriptive, many don’t realise that there is an ability to vary these standards. I firmly believe that there is still the ability to design great apartments even though they may not meet the minimum standard. The ability to vary the standards is often dependent on the design put forward and then assessed. Does the design employ a functional layout? Does the design meet the qualitative objectives of BADS, even though it does not conform to the specs? One of my early concerns with BADS is that we would start to lose the freedom of design and we risk homogeneous outcomes, however the ability to vary the standards paves the way for design that can be innovative, unique and individual.

In theory, there are mechanisms in place to avoid BADS resulting in ‘clipped wings syndrome’, however in reality, these mechanisms are being largely overlooked. At council, we are all too often forced to comply with the standards literally, with council’s using even the slightest hint of non-conformance as a lever to condition or refuse applications. This is a real shame as, ironically, the non-conforming design is usually a better designed apartment.

At VCAT, the picture is a little different as there is a willingness from tribunal members to accept non-conforming solutions so long as it is demonstrated to meet the qualitative measures set by BADS. This is very important to ensuring architects and developers can continue to innovate and inspire with their work. However, from where I’m sitting, there are some serious flaws to this process that need to be reconsidered.

Recently, we have been involved in a number of VCAT cases whereby it is not the architect demonstrating the apartment’s ‘functionality ’ but rather the ‘expert witness’–usually a town planner or an urban designer. I find this incredibly frustrating and concerning for Architects.

How, and why, has our industry cultivated an environment in which consultants are being asked to criticise the functionality of internal spaces, when they would seemingly be unqualified to do so?

As a practice owner and an Architect with over 17 years’ experience navigating the Victorian Planning system, I have the utmost respect for Town and Urban Planners, and the significant role they play in the considered curation of our urban fabric. The work that they do in reviewing and critiquing the external architecture of proposed buildings in relation to the surrounding built environment helps to keep us Architects, as designers, accountable and our solutions considered, ultimately contributing constructively to the development of our cities.

My qualm is not with Planners themselves. Nor is my argument against the crucial role that they play in providing guidance on aspects such as accessibility, liveability, sustainability, and safety in the context of multi-residential design. My issue is with the Planning Scheme, and with the Architects’ bodies that are allowing it to continually dilute our profession.

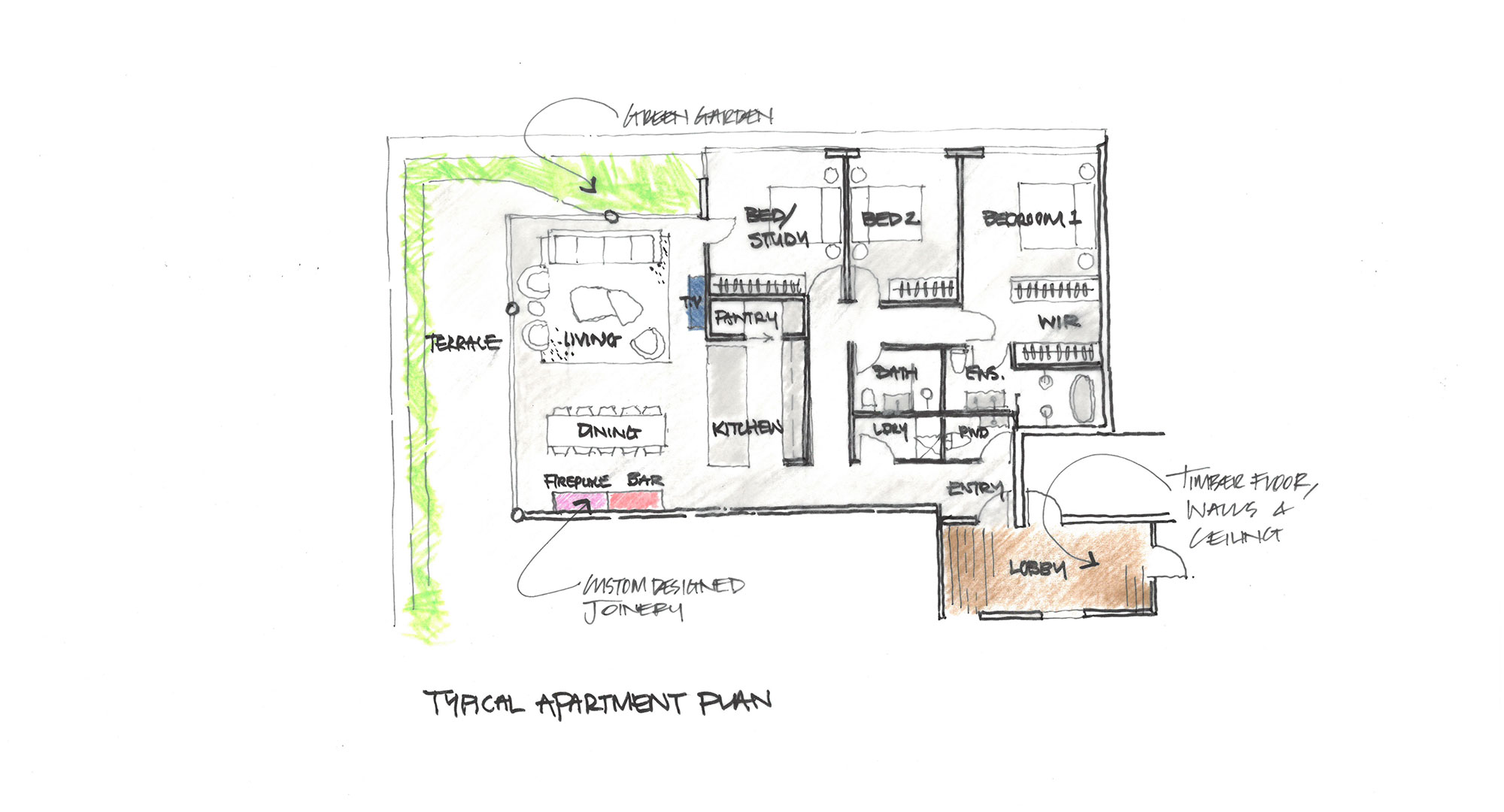

We all can read a plan, assess a plan, and have an opinion on the layout of a dwelling, professionally or not. However I would respectively argue that Architects are best placed to determine that, particularly when a design response calls for a deviation from the standard. As it stands, the assessment of ‘functional internal layouts’ is being reduced to rely so heavily on quantitative measures, that opportunities for more qualitative outcomes are all too often being overlooked because those reviewing them lack the capacity to envision a plan multi-dimensionally. Not only is this risky business in the sense that it is limiting the propensity for design and innovation, but by diluting the assessment of apartment layouts so purely to quantitative measures, we strengthen the case for AI to render the whole process obsolete.

I know I’m not alone in my frustration, having had countless conversations with fellow architects who similarly feel that their work is being thwarted throughout this process. Likewise, I’ve aired these thoughts with my friends and peers in Planning, and have heard what they have to say. Naturally, the majority have argued the importance of having proposals assessed by an independent party–a point with which I wholly agree–and raised concerns about what it would mean to remove Planners from this stage in the process.

Let it be clear that I am not suggesting there should be no review of apartments’ functional internal layouts within the Planning Scheme. That would almost certainly lead to some terrible outcomes, I think we can all agree to that. I am suggesting that when there is a reasonable case for a variation from the cookie-cutter standard, the review process should be referred to an Architect for independent assessment, rather than to a Planner.

While Architects, Town and Urban Planners all have a critical role to play in ensuring that new apartment buildings meet the standards for design, functionality, and safety, it is an Architect’s perspective–that innate ability to ‘see in 3D’–that is needed to duly assess what is or is not a ‘functional internal layout’ in the scheme of multi-residential design.

This article was originally written for and published in the VPELA’s Revue magazine, March 2023.